On one of our recent roadtrips, Andrew and I were listening to ABC national radio. I was enthralled by the lunchtime conversation: Standing for her Convictions: the campaigns of Vida Goldstein

Despite Vida Goldstein being the first woman in the British Empire to nominate for parliament and the first woman in Australia to earn her living as a political activist, I had NEVER heard of her!

It infuriated me that such a woman, or an Australian (of any gender) of such standing, for that matter, has been shamefully omitted from the national curriculum.

In an effort to pursue one cultural agenda, generations of Australians have been denied the opportunity to experience the rich, progressive and unique tapestry that is true Australian history.

As I listened to the story of Vida Goldstein’s life and the many plights she championed, I was alarmed at how many of them still remain.

“Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it”. George Santayana (Spanish born American Philosopher, Poet and Humanist)

The further down the road I traveled, the more I realized the number of parallels between Vida’s world and our own. And I wonder how far have we really come in over 110 years.

The concerns of Vida’s day were changing at a rate that can be compared to the transformation we are now experiencing, with different theories about the nature of society, work, education, and gender. Poverty, for instance, was seen as a problem in need of a solution, with a debate that’s still raging.

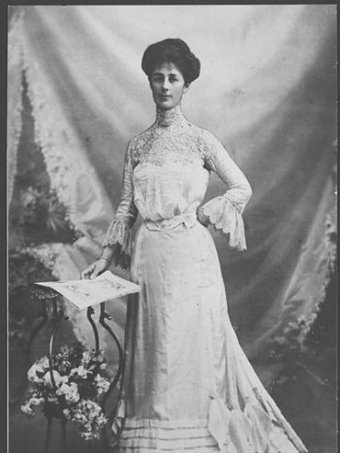

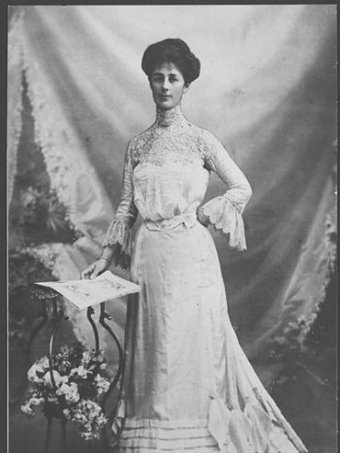

Born the first-child, to devout Christian parents, on 13 April 1869, Vida Jane Mary Goldstein developed a strong social conscience. Her mother, Isabella (née Hawkins) was a very beautiful teetotalling heiress, a suffragist who worked for social reform. Her father, Jacob became heavily involved in charitable and social welfare causes, working closely with the Melbourne Charity Organization Society, the Cheltenham Men’s Home, and the Women’s Hospital Committee. [Goldstein, Vida Jane Mary (1869 – 1949)’] Australian Dictionary of Biography online edition.]

Although Jacob was an anti-suffragist, he strongly believed in education and self-reliance and so engaged a private governess (a suffragist) to educate Vida and her three sisters. Vida later attended the Presbyterian Ladies’ College (1884 – 1886). An education that no doubt came in handy when the family fortune was affected by the depression of the 1890s, and Vida and her sister Aileen, ran the Ingleton co-educational preparatory school in St Kilda.

‘Education’ is a consistent theme that resounds throughout Vida’s life, and I can relate to her compulsion to inform and to be informed.

I should make it very clear from the beginning. I AM NOT a feminist. I do, however, respect those who work to empower women and appreciate the efforts of women (and men) whose suffrage activities highlight that women are equal to men and therefore entitled to the same rights.

In an era characterised by a remarkable polarisation of the sexes; when women’s participation in political life was incredibly limited, with no voting rights, unable to stand for election, all women could do was agitate for change. Vida was initiated into public life in 1891 when a suffrage bill was before the Victorian parliament and her mother recruited the 22-year-old to collect signatures.

It came to be known as the “Monster Petition” when women from all around Victoria managed to collect 33,000 signatures.

Vida later said that this was a great learning experience for her, as she had to learn to argue why women should have the vote when she was door knocking.

In 1899, Goldstein became the first full-time paid organizer for the United Council for Women’s Suffrage at 30 shillings a week. Considering the kind of work Vida would have been doing, 30 shillings seems very fair compared to the average weekly male wage which was approximately 43 shillings a week. [ABS]

While the difference in the kind of work, men and women perform has certainly narrowed, pay differentiation and employment opportunities remain an issue in 2012.

By the turn of the century Vida was heavily involved in forming progressive leagues, such as the Women’s Federal Political Association, which was a network of suburban groups that debated matters of citizenship and women’s rights. These topics were the main features of the monthly journal, the Australian Women’s Sphere, which Vida edited for five years.

She soon became a popular public speaker on women’s issues, orating before packed halls around Australia and in 1902, the same year that Australian women were granted the right to vote in federal elections, Vida made her first trip overseas.

Acknowledged as an influential spokesperson, Vida Goldstein was invited to be the Australian delegate to the International Suffrage Conference in Washington DC, where she was elected Secretary and gave evidence in favour of female suffrage before a committee of the United States Congress. This gave her an international reputation.

While touring the USA, Vida’s associations made the most of her influence:

- The Victorian government asked Vida to investigate the methods of dealing with neglected and delinquent American children.

- The Criminology Society asked her to report back on the US penal system.

- The Trades Hall Council asked her to look at American unions and report on their effectiveness.

- Then the NSW branch of the National Council of Women nominated her as their delegate to attend a conference of the International Council of Women.

Upon her return, Vida gave lectures about her American tour to full halls throughout Victoria – charging admittance and enthralling audiences with her accounts and expertise in matters of social welfare.

At 34 years old, Vida did what no other women had done; she stood for election to the Senate in 1903, as an Independent with the support of the newly formed Women’s Federal Political Association.

Vida was the first woman in the British Empire to stand for election to a national parliament. She saw it as an opportunity to set an example and demonstrate how women were socially capable of being a politician.

“As soon as my candidature was announced, the enemy prophesied a physical breakdown, and humiliating insults from men at my meetings. From all accounts I stood the racket of the campaign better than most of the candidates. After one month’s work, the voices of many were tattered and torn; mine was as fresh and clear the night before the battle as it was when I started skirmishing three months previously.”

Vida failed to secure the Senate seat, winning close to 5% of the total ballots (about half the number of votes of the leading candidate), but she did succeed in changing perceptions of women in politics.

Undeterred, the loss prompted her to concentrate on female education and political organisation, including the National Council of Women, the Victorian Women’s Public Servants’ Association and the Women Writers’ Club.

In 1909, having closed the Australian Women’s Sphere journal in 1905 in order to dedicate herself more fully to the campaign for female suffrage in Victoria, she founded a second newspaper – Woman Voter. It became a supporting mouthpiece for women’s rights and emancipation and later promoted her political campaigns. [Lees, Kirsten (1995) Votes for Women: The Australian Story St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, p. 146]

She actively lobbied parliament on issues such as:

- Equality of property rights,

- Birth control,

- Equal Naturalisation laws,

- The creation of a system of children’s courts, and

- Raising the age of marriage consent.

All issues that remain in contention today, around the world.

Defiant, she stood for parliament again in 1910, 1913 and 1914; her fifth and last bid was in 1917 for a Senate seat on the principle of international peace, a position that ultimately, lost her votes.

In the hope that her experience would help them with their battles for the vote, Goldstein visited England in 1911, at the behest of the Women’s Social and Political Union.

Her lectures drew massive crowds, from around the country and was touted as “the biggest thing that has happened in the women movement for sometime in England”. [Alice Henry (1911) Vida Goldstein Papers, 1902-1919. LTL:V MSS 7865]

Seen as an expert, Vida was also put in charge of the foreign contingent of a huge demonstration of 40,000 women. It would have been an amazing site to see, the procession of so many women, congregated and all dressed in white with the suffrage colours of purple, white and green.

Her trip in England concluded with the foundation of the Australia and New Zealand Women Voters Association, an organisation dedicated to ensuring that the British Parliament would not undermine suffrage laws in the colonies.

Women did not receive the right to vote in the United Kingdom (including Ireland) until 1918 and it took another 2 years for the USA to follow.

In 1915 Vida formed the Women’s Peace Army and became chairman of the Peace Alliance. An ardent pacifist, before and throughout the Boer and First World Wars, uncompromising in her position, Vida founded this antiwar group shortly after the futile loss of life at Gallipoli. She rigorously campaigned against conscription for the 1916 referendum, organizing a procession; the very first time that Australian women marched in a peace demonstration.

At the end of the First World War, Vida retreated from public life, although she wrote articles campaigning for a number of public causes. In 1919 she accepted an invitation to represent Australian women at a Women’s Peace Conference in Zurich and spoke out against the atomic bomb during WWII.

In the last decades of her life her focus turned more intently to her faith and spirituality. She became increasingly involved with the Christian Science movement – whose Melbourne church she helped found.

Despite many suitors, Vida never married and there is no suggestion of any intimate relationship. She lived in her last years quietly with her unmarried sister Aileen and her widowed sister Elsie. She died of cancer in South Yarra on 15 August 1949 at the age of 80, and, in line with her beliefs, she was cremated.

Vida Goldstein’s death passed almost unnoticed, and it wasn’t really until the 1970s with “Second Wave Feminism” before she was recognized as a pioneer suffragist and important figure in Australian social history.

Whether you agree with all the aspects of her politics or not, it is figures like Vida, who are a source of inspiration for many female generations.

Whilst I do not necessarily agree with all of Vida’s campaigns, I respect her tenacity, energy and skill in carving out a role for herself in Australian politics, when other women had previously only sat on the sidelines.

I think her great contribution was leading by example. Showing that a woman could be innovative and daring and demonstrating all that could be achieved, by sticking to her convictions and without compromising her femininity, in a time when questions were being asked about what did constitute womanliness.

It goes to show that the media has not changed in over a century as they still insist on commenting on the female advocate’s fashion rather than the substance of her policy:

“Miss Goldstein presented a very pleasing appearance on the platform at Avoca. She was graceful, prettily gowned, and wore a most becoming hat. — The Ararat Advertiser, 27th October 1903.

Vs.

“What I want [Julia] to do is get rid of those bloody jackets! It’s not even fashion…they don’t fit! You’ve got a big arse, Julia!” Germaine Greer Q&A

At least the media of the day noted Vida’s oratory skills and ability to communicate her ideas.

“She is nice to look at and absolutely delightful to listen to. The quick, eager way she has of rising to answer questions has its charms, for you see there the enthusiasm. Her smartness at repartee is a rare gift. Her composure when signs of disturbance appear and the way she has of getting off a slap at the other side, without in the least descending from the pedestal she as a lady stands on, are worth seeing and hearing.

— West Gippsland Gazette, 1st December, 1903.

With the scapegoat appointments and inevitable downfall of Bligh, Kenelley and Gillard, it seems as though female politicians in roles of true leadership, are as much of a novelty now as they were at the turn of the Twentieth Century. So how far have we really come?

Honestly, I believe we have come leaps and bounds and I do not believe the above-mentioned women can even be considered in the same league as Vida Goldstein. Vida’s views and actions were incredibly radical and unlike so many politicians of our day, she managed to holdfast to the courage of her convictions; communicate her agenda through positive media coverage, and compel those least likely to listen, to at least come and hear her.

Few politicians today can boast such a balance of their principles between their party’s short-sighted, vote-chasing platforms and a well orchestrated but genuine public image.

A remarkable example of an enfranchised woman of her time, I love Vida’s passion for sharing ideas to a less than receptive audience, a young and attractive woman talking about the sorts of things that a great many men thought women shouldn’t bother their pretty “little” heads with.

You cannot help but admire her commitment to social justice, social change and gracious contempt for authority.

As editor of The Woman Voter newspaper, Vida was annoyed by the War Precautions Act and having to submit all her copy to the censor before publication. When Prime Minister Billy Hughes introduced even more severe censorship, Vida rebelled by publishing “Mr Hughes says we may have a free press” in spare spaces of the journal.

Now in Australia in the Twenty-First century there can be little doubt freedom of the press and the expectation that you can freely speak your mind is under threat. The Gillard Government’s media inquiry, the Finkelstein Report, threatens not only our freedom to speak, but to listen and make decisions for ourselves. Learn more by clicking here.

The recommendations of the Finkelstein Report would only catapult us back into the Dark Ages, when we are standing on the edge of an exciting frontier in information and education.

It is figures like Vida Goldstein who speak out about oppression and social justice who should be featured heavily in our national curriculum to demonstrate the true pioneering nature of our citizens and the importance of learning lessons from our past.

The only way to make sure people you agree with can speak is to support the rights of people you don’t agree with.

– Eleanor Holmes Norton

CELEBRATE Vida and all her achievements by sharing this on the facebook walls and Twitter Feeds of all those women you admire and respect!

For more details about Vida’s amazing life check out the following recommended Publications

- Title

- Votes for Women: The Australian Story

- Author

- Lees, Kirsten

- Publisher

- St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1995

- Title

- A great idea : peace and women politicians of Victoria

- Author

- Margaret Geddes

- Publisher

- League of Women Voters of Victoria, 1987 Gardenvale, Vic.

- Title

- Passions of the First Wave Feminists

- Author

- Susan Magarey

- Publisher

- UNSW Press, 2001, Sydney

- Title

- Double Time: women in Victoria 150 years

- Author

- Farley Kelly & Marilyn Lake

- Publisher

- Penguin Books, 1985 Ringwood, Vic

- Title

- Victorian Historical Journal, Women’s Suffrage Centenary Issue Nov 2008

- Author

- Joy Damousi & Shurlee Swain

- Publisher

- Royal Historical Society of Victoria

- Title

- The Life and Work of Miss Vida Goldstein

- Author

- Women’s Political Association.

- Publisher

- Melbourne: Australasian Authors’ Agency

- Title

- The Goldstein Story

- Author

- L M Henderson

- Publisher

- Melbourne 1973

- Title

- That dangerous and persuasive woman : Vida Goldstein

- Author

- Janette M. Bomford

- Publisher

- Melbourne University Press, 1993 Carlton, Vic.

CELEBRATE Vida and all her achievements by sharing your stories of inspiration and of characters you admire.

Follow up on the interest created by your Thought Leadership. Don’t take your popularity for granted. Create closed or invite/members-only groups.

Follow up on the interest created by your Thought Leadership. Don’t take your popularity for granted. Create closed or invite/members-only groups.